5.1 Linear Model

Linear models have been used for a long time by statisticians, computer scientists, and other people tackling quantitative problems. Linear models learn linear (and therefore monotonic) relationships between the features and the target. The linearity of the learned relationship makes the interpretation easy.

Linear models can be used to model the dependency of a regression target \(y\) on \(p\) features \(x\). The learned relationships are linear and, for a singular instance \(i\), can be written as:

\[y_{i}=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}x_{i1}+\ldots+\beta_{p}x_{ip}+\epsilon_{i}\]

The i-th instance’s outcome is a weighted sum of its \(p\) features. The \(\beta_{j}\) represent the learned feature weights or coefficients. The \(\epsilon_{i}\) is the error we are still making, i.e. the difference between the predicted outcome and the actual outcome.

Different methods can be used to estimate the optimal weight vector \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\). The ordinary least squares method is commonly used to find the weights that minimise the squared difference between the actual and the estimated outcome:

\[\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}=\arg\!\min_{\beta_0,\ldots,\beta_p}\sum_{i=1}^n\left(y_i-\left(\beta_0+\sum_{j=1}^p\beta_jx_{ij}\right)\right)^{2}\]

We won’t go into detail about how the optimal weights can be found, but if you are interested you can read Chapter 3.2 of the book “Elements of Statistical Learning” (Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman 2009)13 or one of the other zillions of sources about linear regression models.

The biggest advantage of linear regression models is their linearity: It makes the estimation procedure straightforward and, most importantly, these linear equations have an easy to understand interpretation on a modular level (i.e. the weights). That is one of the main reasons why the linear model and all similar models are so widespread in academic fields like medicine, sociology, psychology, and many more quantitative research fields. In these areas it is important to not only predict, e.g., the clinical outcome of a patient, but also to quantify the influence of the medication while at the same time accounting for things like gender, age, and other features in an interpretable manner. Estimates of coefficients or weights also comes with confidence intervals. A confidence interval is a range for the weight estimate that covers the ‘true’ parameter with a certain confidence. For example, a 95% confidence interval for a weight of 2 could range from 1 to 3 and its interpretation would be: If we repeated the estimation 100 times with newly sampled data, the confidence interval would cover the true parameter in 95 out of 100 cases.

Linear regression models also come with some assumptions that make them easy to use and interpret but which are often not satisfied in reality. The assumptions are: Linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, independence, fixed features, and absence of multicollinearity.

- Linearity: Linear regression models force the estimated response to be a linear combination of the features, which is both their greatest strength and biggest limitation. Linearity leads to interpretable models: linear effects are simple to quantify and describe (see also next chapter) and are additive, so it is easy to separate the effects. If you suspect interactions of features or a non-linear association of a feature with the target value, then you can add interaction terms and use techniques like regression splines to estimate non-linear effects.

- Normality: The target outcome given the features are assumed to follow a normal distribution. If this assumption is violated, then the estimated confidence intervals of the feature weights are not valid. Consequently, any interpretation of the features p-values is not valid.

- Homoscedasticity (constant variance): The variance of the error terms \(\epsilon_{i}\) is assumed to be constant over the whole feature space. Let’s say you want to predict the value of a house given the living area in square meters. You estimate a linear model, which assumes that no matter how big the house, the error terms around the predicted response have the same variance. This assumption is often violated in reality. In the house example it is plausible that the variance of error terms around the predicted price is higher for bigger houses, since also the prices are higher and there is more room for prices to vary.

- Independence: Each instance is assumed to be independent from the next one. If you have repeated measurements, like multiple records per patient, the data points are not independent from each other and there are special linear model classes to deal with these cases, like mixed effect models or GEEs.

- Fixed features: The input features are seen as ‘fixed’, carrying no errors or variation, which, of course, is very unrealistic and only makes sense in controlled experimental settings. But not assuming fixed features would mean that you have to fit very complex measurement error models that account for the measurement errors of your input features. And usually you don’t want to do that.

- Absence of multicollinearity: Basically you don’t want features to be highly correlated, because this messes up the estimation of the weights. In a situation where two features are highly correlated (something like correlation > 0.9) it will become problematic to estimate the weights, since the feature effects are additive and it becomes indeterminable to which of the correlated features to attribute the effects.

5.1.1 Interpretation

The interpretation of a weight in the linear model depends on the type of the corresponding feature:

- Numerical feature: For an increase of the numerical feature \(x_{j}\) by one unit, the estimated outcome changes by \(\beta_{j}\). An example of a numerical feature is the size of a house.

- Binary feature: A feature, that for each instance takes on one of two possible values. An example is the feature “House comes with a garden”. One of the values counts as the reference level (in some programming languages coded with 0), like “No garden”. A change of the feature \(x_{j}\) from the reference level to the other level changes the estimated outcome by \(\beta_{j}\).

- Categorical feature with multiple levels: A feature with a fixed amount of possible values. An example is the feature “Flooring type”, with possible levels “carpet”, “laminate” and “parquet”. One solution to deal with many levels is to one-hot-encode them, meaning each level gets its own binary column. From a categorical feature with \(l\) levels, you only need \(l-1\) columns, otherwise the coding is overparameterised. The interpretation for each level is then according to the binary features. Some languages, like R, allow you to code categorical features in different ways, described here.

- Intercept \(\beta_{0}\): The intercept is the feature weight for the constant feature, which is always 1 for all instances. Most software packages automatically add this feature for estimating the intercept. The interpretation is: Given all numerical features are zero and the categorical features are at the reference level, the estimated outcome of \(y_{i}\) is \(\beta_{0}\). The interpretation of \(\beta_{0}\) is usually not relevant, because instances with all features at zero often don’t make any sense, unless the features were standardised (mean of zero, standard deviation of one), where the intercept \(\beta_0\) reflects the predicted outcome of an instance where all features are at their mean.

Another important measurement for interpreting linear models is the \(R^2\) measurement. \(R^2\) tells you how much of the total variance of your target outcome is explained by the model. The higher \(R^2\) the better your model explains the data. The formula to calculate \(R^2\) is: \(R^2=1-SSE/SST\), where SSE is the squared sum of the error terms:

\[SSE=\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-\hat{y}_i)^2\]

and SST is the squared sum of the data variance:

\[SST=\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-\bar{y})^2\]

The SSE tells you how much variance remains after fitting the linear model, which is measured by looking at the squared differences between the predicted and actual target values. SST is the total variance of the target around the mean. So \(R^2\) tells you how much of your variance can be explained by the linear model. \(R^2\) ranges between 0 for models that explain nothing and 1 for models that explain all of the variance in your data.

There is a catch, because \(R^2\) increases with the number of features in the model, even if they carry no information about the target value at all. So it is better to use the adjusted R-squared (\(\bar{R}^2\)), which accounts for the number of features used in the model. Its calculation is

\[\bar{R}^2=R^2-(1-R^2)\frac{p}{n-p-1}\],

where \(p\) is the number of features and \(n\) the number of instances.

It isn’t helpful to do interpretation on a model with very low \(R^2\) or \(\bar{R}^2\), because basically the model is not explaining much of the variance, so any interpretation of the weights are not meaningful.

5.1.2 Interpretation Example

In this example we use the linear model to predict the number of rented bikes on a day, given weather and calendrical information. For the interpretation we examine the estimated regression weights. The features are a mix of numerical and categorical features. The table shows for each feature the estimated weight and the standard error of the estimation:

| Weight estimate | Std. Error | |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2399.4 | 238.3 |

| seasonSUMMER | 899.3 | 122.3 |

| seasonFALL | 138.2 | 161.7 |

| seasonWINTER | 425.6 | 110.8 |

| holidayHOLIDAY | -686.1 | 203.3 |

| workingdayWORKING DAY | 124.9 | 73.3 |

| weathersitMISTY | -379.4 | 87.6 |

| weathersitRAIN/SNOW/STORM | -1901.5 | 223.6 |

| temp | 110.7 | 7.0 |

| hum | -17.4 | 3.2 |

| windspeed | -42.5 | 6.9 |

| days_since_2011 | 4.9 | 0.2 |

Interpretation of a numerical feature (‘Temperature’): An increase of the temperature by 1 degree Celsius increases the expected number of bikes by 110.7, given all other features stay the same.

Interpretation of a categorical feature (‘weathersituation’)): The estimated number of bikes is -1901.5 lower when it is rainy, snowing or stormy, compared to good weather, given that all other features stay the same. Also if the weather was misty, the expected number of bikes was -379.4 lower, compared to good weather, given all other features stay the same.

As you can see in the interpretation examples, the interpretations always come with the footnote that ‘all other features stay the same’. That’s because of the nature of linear models: The target is a linear combination of the weighted features. The estimated linear equation spans a hyperplane in the feature/target space (a simple line in the case of a single feature). The \(\beta\) (weight) values specify the slope (gradient) of the hyperplane in each direction. The good side is that it isolates the interpretation. If you think of the features as knobs that you can turn up or down, it is nice to see what happens when you would just turn the knob for one feature. On the bad side of things, the interpretation ignores the joint distribution with other features. Increasing one feature, but not changing others, might create unrealistic, or at least unlikely, data points.

5.1.3 Interpretation templates

The interpretation of the features in the linear model can be automated by using following text templates.

Interpretation of a Numerical Feature

An increase of \(x_{k}\) by one unit increases the expectation for \(y\) by \(\beta_k\) units, given all other features stay the same.

Interpretation of a Categorical Feature

A change from \(x_{k}\)’s reference level to the other category increases the expectation for \(y\) by \(\beta_{k}\), given all other features stay the same.

5.1.4 Visual parameter interpretation

Different visualisations make the linear model outcomes easy and quick to grasp for humans.

5.1.4.1 Weight plot

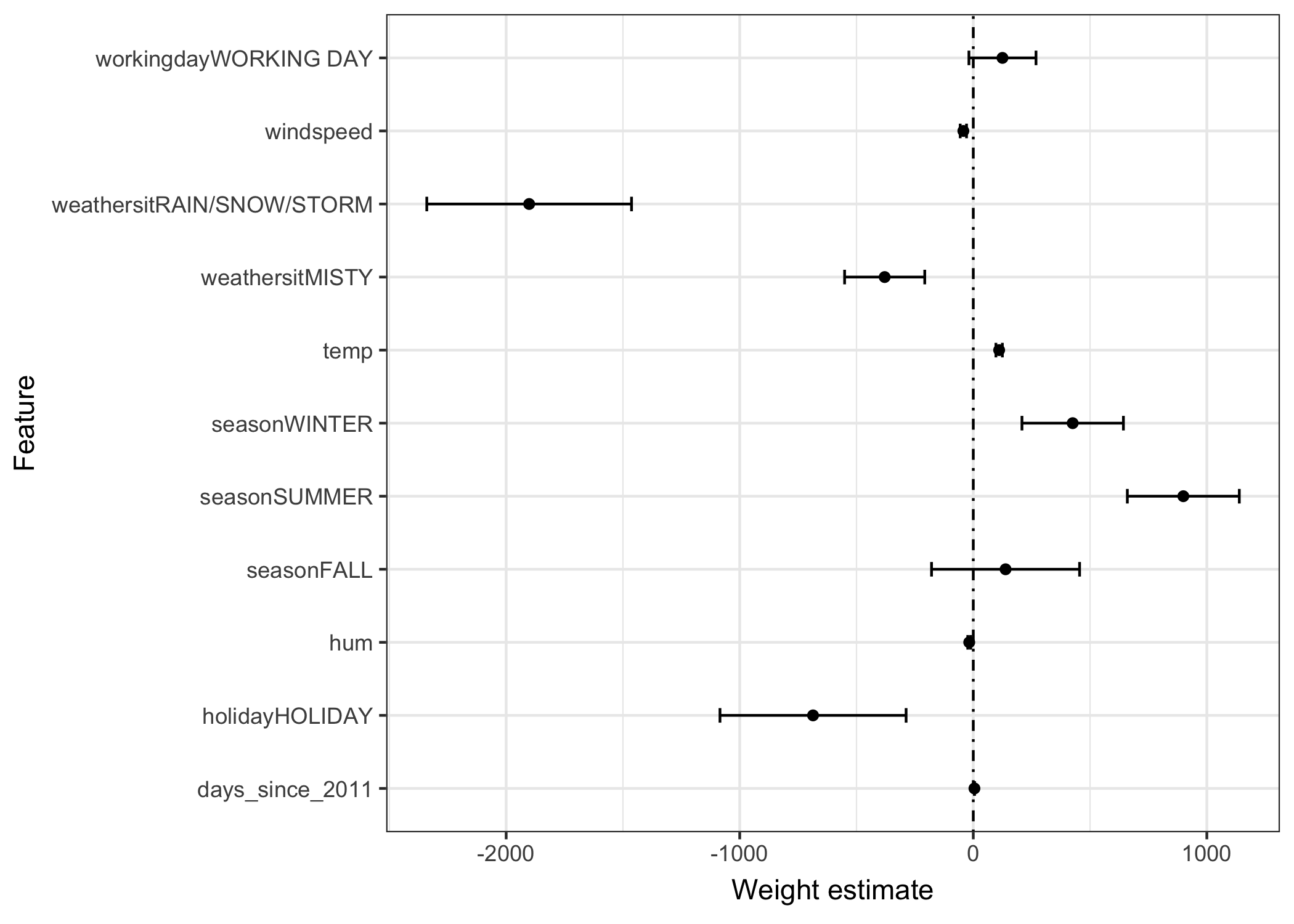

The information of the weights table (weight estimates and variance) can be visualised in a weight plot (showing the results from the linear model fitted before):

FIGURE 5.1: Each row in the plot represents one feature weight. The weights are displayed as points and the 0.95 confidence intervals with a line around the points. A 0.95 confidence interval means that if the linear model would be estimated 100 times on similar data, in 95 out of 100 times, the confidence interval would cover the true weight, under the linear model assumptions (linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, independence, fixed features, absence of multicolinearity).

The weight plot makes clear that rainy/snowy/stormy weather has a strong negative effect on the expected number of bikes. The working day feature’s weight is close to zero and the zero is included in the 95% interval, meaning it is not influencing the prediction significantly. Some confidence intervals are very short and the estimates are close to zero, yet the features were important. Temperature is such a candidate. The problem about the weight plot is that the features are measured on different scales. While for weather situation feature the estimated \(\beta\) signifies the difference between good and rainy/storm/snowy weather, for temperature it signifies only an increase of 1 degree Celsius. You can improve the comparison by scaling the features to zero mean and unit standard deviation before fitting the linear model, to make the estimated weights comparable.

5.1.4.2 Effect Plot

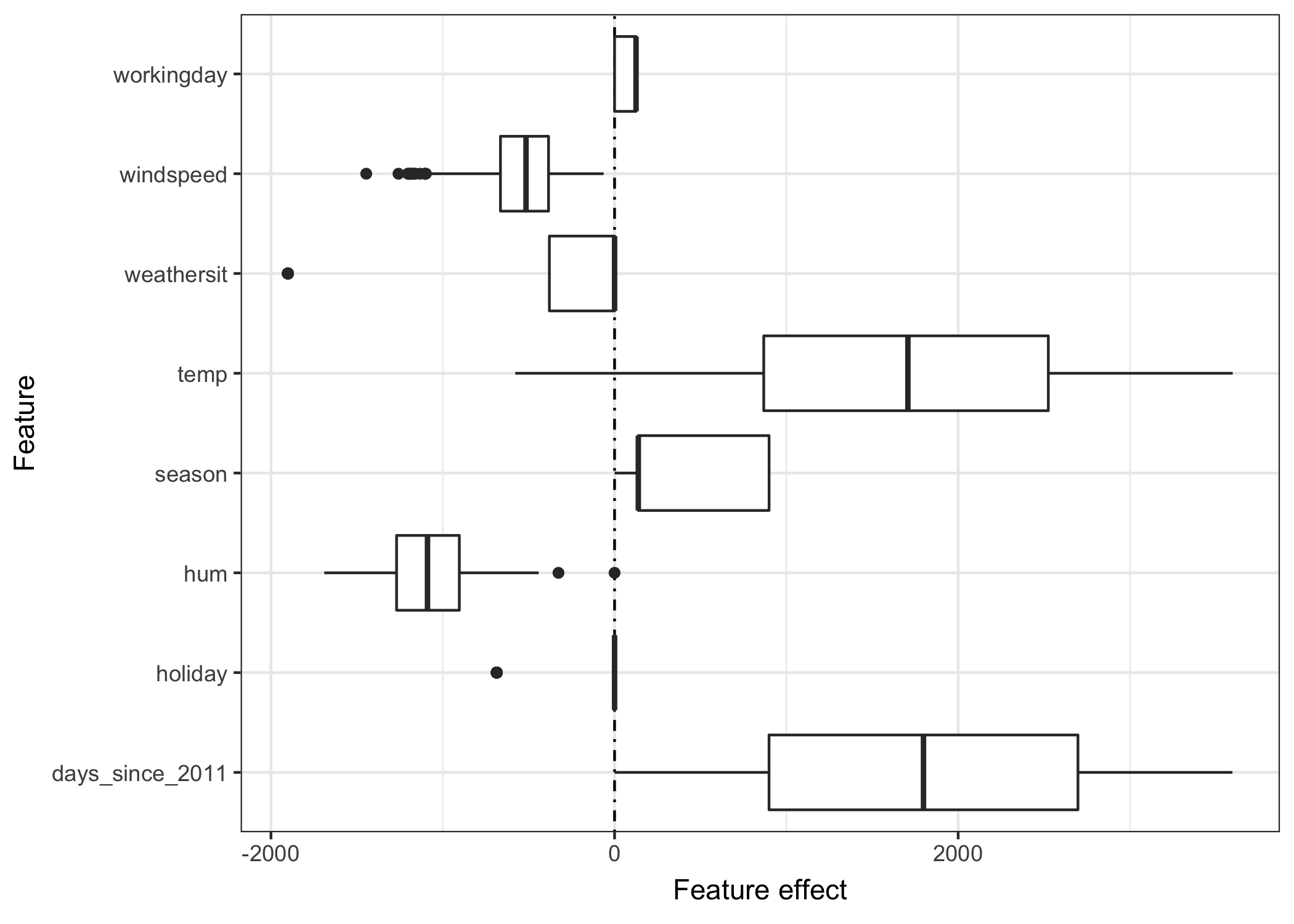

The weights of the linear model can be analysed more meaningfully when multiplied by the actual feature values. The weights depend on the scale of the features and will be different if you have a feature measuring some height and you switch from meters to centimetres. The weight will change, but the actual relationships in your data will not. It is also important to know the distribution of your feature in the data, because if you have a very low variance, it means that almost all instances will get a similar contribution from this feature. The effect plot can help to understand how much the combination of a weight and a feature contributes to the predictions in your data. Start with the computation of the effects, which is the weight per feature times the feature of an instance: \(\text{effect}_{i,j}=w_{j}x_{i,j}\). The resulting effects are visualised with boxplots: A box in a boxplot contains the effect range for half of your data (25% to 75% effect quantiles). The vertical line in the box is the median effect, i.e. 50% of the instances have a lower and the other half a higher effect on the prediction than the median value. The horizontal lines extend to\(\pm1.58\text{IQR}/\sqrt{n}\), with IQR being the inter quartile range (\(q_{0.75}-q_{0.25}\)). The points are outliers. The categorical feature effects can be aggregated into one boxplot, compared to the weight plot, where each weight gets a row.

FIGURE 5.2: The feature effect plot shows the distribution of the effects (= feature value times feature weight) over the dataset for each feature.

The largest contributions to the expected number of rented bikes comes from temperature and from the days feature, which captures the trend that the bike rental became more popular over time. The temperature has a broad contribution distribution. The day trend feature goes from zero to large positive contribution, because the first day in the dataset (01.01.2011) gets a very low day effect, and the estimated weight with this feature is positive (4.93), so the effect increases with every day and is highest for the latest day in the dataset (31.12.2012). Note that for effects from a feature with a negative weight, the instances with a positive effect are the ones that have a negative feature value, so days with a high negative effect of windspeed on the bike count have the highest windspeeds.

5.1.5 Explaining Single Predictions

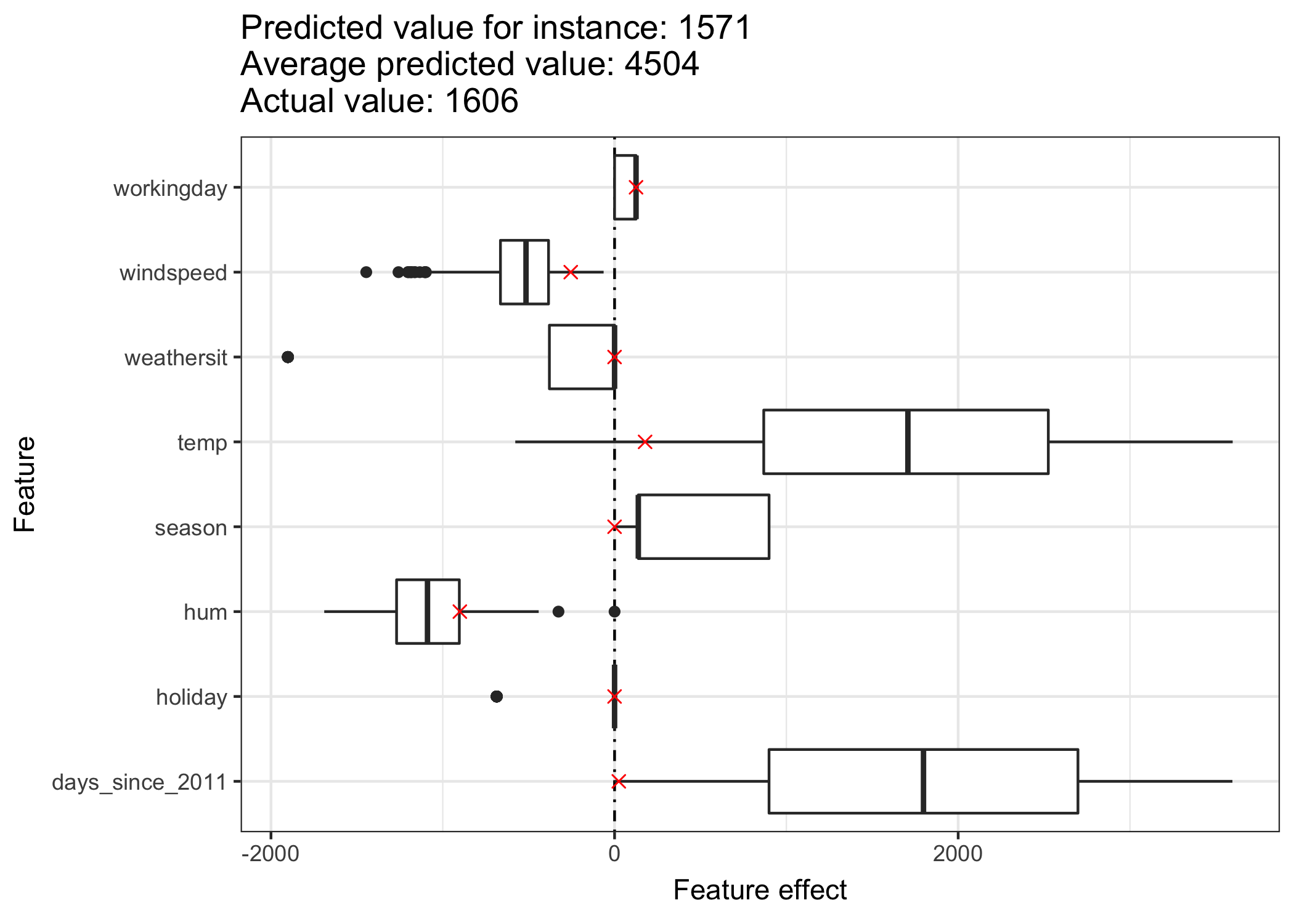

How much did each feature of an instance contribute towards the prediction? This can, again, be answered by bringing together the weights and feature values of this instance and computing the effects. An interpretation of instance specific effects is only meaningful in comparison with the distribution of each feature’s effects.

FIGURE 5.3: The effect for one instance shows the effect distribution while highlighting the effects of the instance of interest.

Let’s have a look at the effect realisation for the bike count of one instance (i.e. one day). Some features contribute unusually little or much to the predicted bike count when compared to the overall dataset: Temperature (2 degrees) contributes less towards the predicted value compared to the average and the trend feature “days_since_2011” unusually much, because this instance is from late 2011 (5 days).

5.1.6 Coding Categorical Features

There are several ways to encode a categorical feature and the choice influences the interpretation of the \(\beta\)-weights.

The standard in linear regression models is the treatment coding, which is sufficient in most cases. Using different codings boils down to creating different matrices (=design matrix) from your one column with the categorical feature. This section presents three different codings, but there are many more. The example used has six instances and one categorical feature with 3 levels. For the first two instances, the feature takes on category A, for instances three and four category B and for the last two instances category C.

Treatment coding:

The \(\beta\) per level is the estimated difference in \(y\) compared to the reference level. The intercept of the linear model is the mean of the reference group (given all other features stay the same). The first column of the design matrix is the intercept, which is always 1. Column two is an indicator whether instance \(i\) is in category B, column three is an indicator for category C. There is no need for a column for category A, because then the linear equation would be overspecified and no unique solution (= unique \(\beta\)’s) can be found. Knowing that an instance is neither in category B or C is enough.

Feature matrix: \[\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&0\\1&1&0\\1&1&0\\1&0&1\\1&0&1\\\end{pmatrix}\]

Effect coding:

The \(\beta\) per level is the estimated \(y\)-difference from the level to the overall mean (again, given all other features are zero or the reference level). The first column is again used to estimate the intercept. The weight \(\beta_{0}\) which is associated with the intercept represents the overall mean and \(\beta_{1}\), the weight for column two is the difference between the overall mean and category B. The overall effect of category B is \(\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}\). The interpretation for category C is equivalent. For the reference category A, \(-(\beta_{1}+\beta_{2})\) is the difference to the overall mean and \(\beta_{0}-(\beta_{1}+\beta_{2})\) the overall effect.

Feature matrix: \[\begin{pmatrix}1&-1&-1\\1&-1&-1\\1&1&0\\1&1&0\\1&0&1\\1&0&1\\\end{pmatrix}\]

Dummy coding:

The \(\beta\) per level is the estimated mean of \(y\) for each level (given all feature are at value zero or reference level). Note that the intercept was dropped here, so that a unique solution for the linear model weights can be found.

Feature matrix: \[\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&0\\0&1&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&1\\0&0&1\\\end{pmatrix}\]

If you want to dive a bit deeper into different encodings of categorical features, checkout this webpage and this blog post.

5.1.7 The disadvantages of linear models

Linear models can only represent linear relationships. Each non-linearity or interaction has to be hand-crafted and explicitly given to the model as an input feature.

Linear models are also often not that good regarding predictive performance, because the relationships that can be learned are so restricted and usually oversimplifies how complex reality is.

The interpretation of a weight can be unintuitive because it depends on all other features. A feature with high positive correlation with the outcome \(y\) and another feature might get a negative weight in the linear model, because, given the other correlated feature, it is negatively correlated with \(y\) in the high-dimensional space. Completely correlated features make it even impossible to find a unique solution for the linear equation. An example: You have a model to predict the value of a house and have features like number of rooms and area of the house. House area and number of rooms are highly correlated: the bigger a house is, the more rooms it has. If you now take both features into a linear model, it might happen, that the area of the house is the better predictor and get’s a large positive weight. The number of rooms might end up getting a negative weight, because either, given that a house has the same size, increasing the number of rooms could make it less valuable or the linear equation becomes less stable, when the correlation is too strong.

5.1.8 Do linear models create good explanations?

Judging by the attributes that constitute a good explanation as presented in this section, linear models don’t create the best explanations. They are contrastive, but the reference instance is a data point for which all continuous features are zero and the categorical features at their reference levels. This is usually an artificial, meaningless instance, which is unlikely to occur in your dataset. There is an exception: When all continuous features are mean centered (feature minus mean of feature) and all categorical features are effect coded, the reference instance is the data point for which each feature is at its mean. This might also be a non-existent data point, but it might be at least more likely or meaningful. In this case, the \(\beta\)-values times the feature values (feature effects) explain the contribution to the predicted outcome contrastive to the reference mean-instance. Another aspect of a good explanation is selectivity, which can be achieved in linear models by using less features or by fitting sparse linear models. But by default, linear models don’t create selective explanations. Linear models create truthful explanations, as long as the linear equation can model the relationship between features and outcome. The more non-linearities and interactions exist, the less accurate the linear model becomes and the less truthful explanations it will produce. The linearity makes the explanations more general and simple. The linear nature of the model, I believe, is the main factor why people like linear models for explaining relationships.

5.1.9 Extending Linear Models

Linear models have been extensively studied and extended to fix some of the shortcomings.

- Lasso is a method to “pressure” weights of irrelevant features to get an estimate of zero. Having unimportant features weighted by zero is useful, because having less terms to interpret makes the model more interpretable.

- Generalised linear models (GLM) allow the target outcome to have different distributions. The target outcome is not any longer required to be normally distributed given the features, but GLMs allow you to model for example Poisson distributed count variables. Logistic regression, is a GLM for categorical outcomes.

- Generalised additive models (GAMs) are GLMs with the additional ability to allow non-linear relationships with features, while maintaining the linear equation structure (sounds paradox, I know, but it works).

You can also apply all sorts of tricks to go around some of the problems:

- Adding interactions: You can define interactions between features and add them as new features before estimating the linear model. The RuleFit algorithm can add interactions automatically.

- Adding non-linear terms like polynomials to allow non-linear relationships with features.

- Stratifying data by feature and fitting linear models on subsets.

5.1.10 Sparse linear models

The examples for the linear models that I chose look all nice and tidy, right? But in reality you might not have just a handful of features, but hundreds or thousands. And your normal linear models? Interpretability goes downriver. You might even get into a situation with more features than instances and you can’t fit a standard linear model at all. The good news is that there are ways to introduce sparsity (= only keeping a few features) into linear models.

5.1.10.1 Lasso

The most automatic and convenient way to introduce sparsity is to use the Lasso method. Lasso stands for “least absolute shrinkage and selection operator” and when added to a linear model, it performs feature selection and regularisation of the selected feature weights. Let’s review the minimization problem, the \(\beta\)s optimise:

\[min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-x_i^T\boldsymbol{\beta})^2\right)\]

Lasso adds a term to this optimisation problem:

\[min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-x_i^T\boldsymbol{\beta})^2+\lambda||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_1\right)\]

The term \(||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_1\), the L1-norm of the feature vector, leads to a penalisation of large \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)-values. Since the L1-norm is used, many of the weights for the features will get an estimate of 0 and the others are shrunk. The parameter \(\lambda\) controls the strength of the regularising effect and is usually tuned by doing cross-validation. Especially when \(\lambda\) is large, many weights become 0.

5.1.10.2 Other Methods for Sparsity in Linear Models

A big spectrum of methods can be used to reduce the number of features in a linear model.

Methods that include a pre-processing step:

- Hand selected features: You can always use expert knowledge to choose and discard some features. The big drawback is, that it can’t be automated and you might not be an expert.

- Use some measures to pre-select features: An example is the correlation coefficient. You only take features into account that exceed some chosen threshold of correlation between the feature and the target. Disadvantage is that it only looks at the features one at a time. Some features might only show correlation after the linear model has accounted for some other features. Those you will miss with this approach.

Step-wise procedures:

- Forward selection: Fit the linear model with one feature. Do that with each feature. Choose the model that works best (for example decided by the highest R squared). Now again, for the remaining features, fit different versions of your model by adding each feature to your chosen model. Pick the one that performs best. Continue until some criterium is reached, like the maximum number of features in the model.

- Backward selection: Same as forward selection, but instead of adding features, start with the model that includes all features and try out which feature you have to remove to get the highest performance increase. Repeat until some stopping criterium is reached.

I recommend using Lasso, because it can be automated, looks at all features at the same time and can be controlled via \(\lambda\). It also works for the logistic regression model for classification.

Hastie, T, R Tibshirani, and J Friedman. 2009. The elements of statistical learning. http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-0-387-84858-7.pdf.↩